Gender Pay Gap and Recruitment Processes in Estonia

2025 | user research

I'm currently participating in the Student Service Design Challenge, for which I researched the gender pay gap and recruitment processes. At the beginning of the challenge, our team chose to tackle the initial brief presented by IBM, which generally focused on the topic of bias or cognitive biases.

Result: We have reached the finals of the Student Service Design Challenge.

Team

Gabriella Tarja

Hanna Milk

Helen Kärt Käbin

Kairiin Koddala

Laura Sööt

Paula Maria Mengel

My Role:

Research – background research, creating surveys, data analysis, conducting interviews.

Stage

Initial Brief

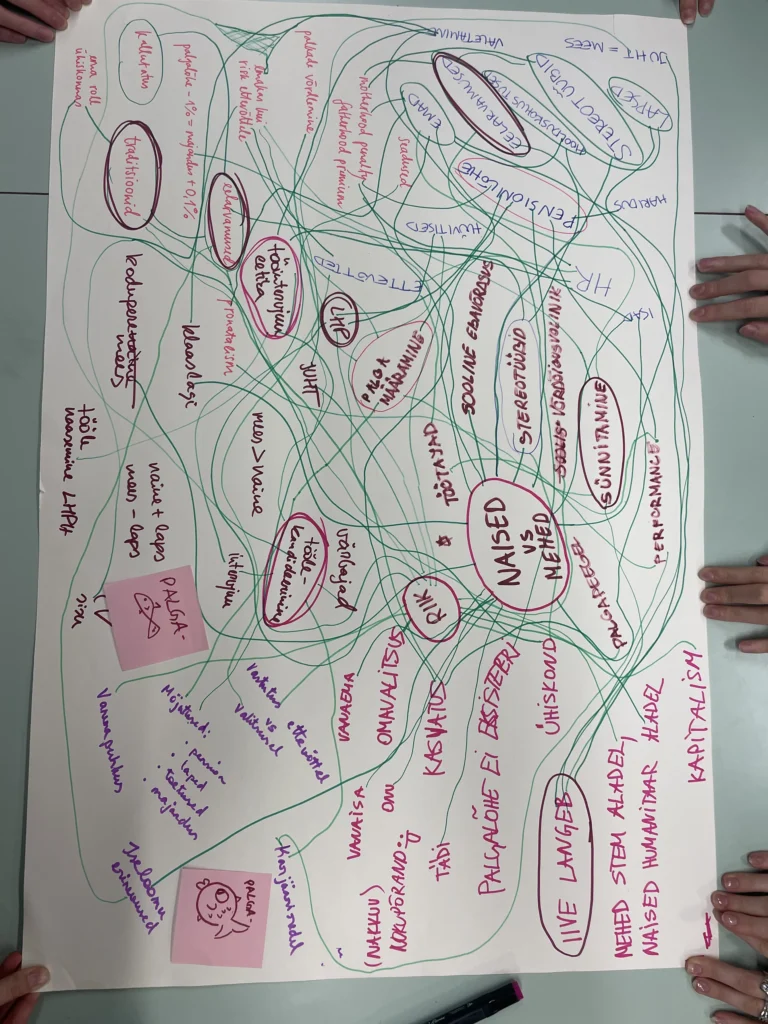

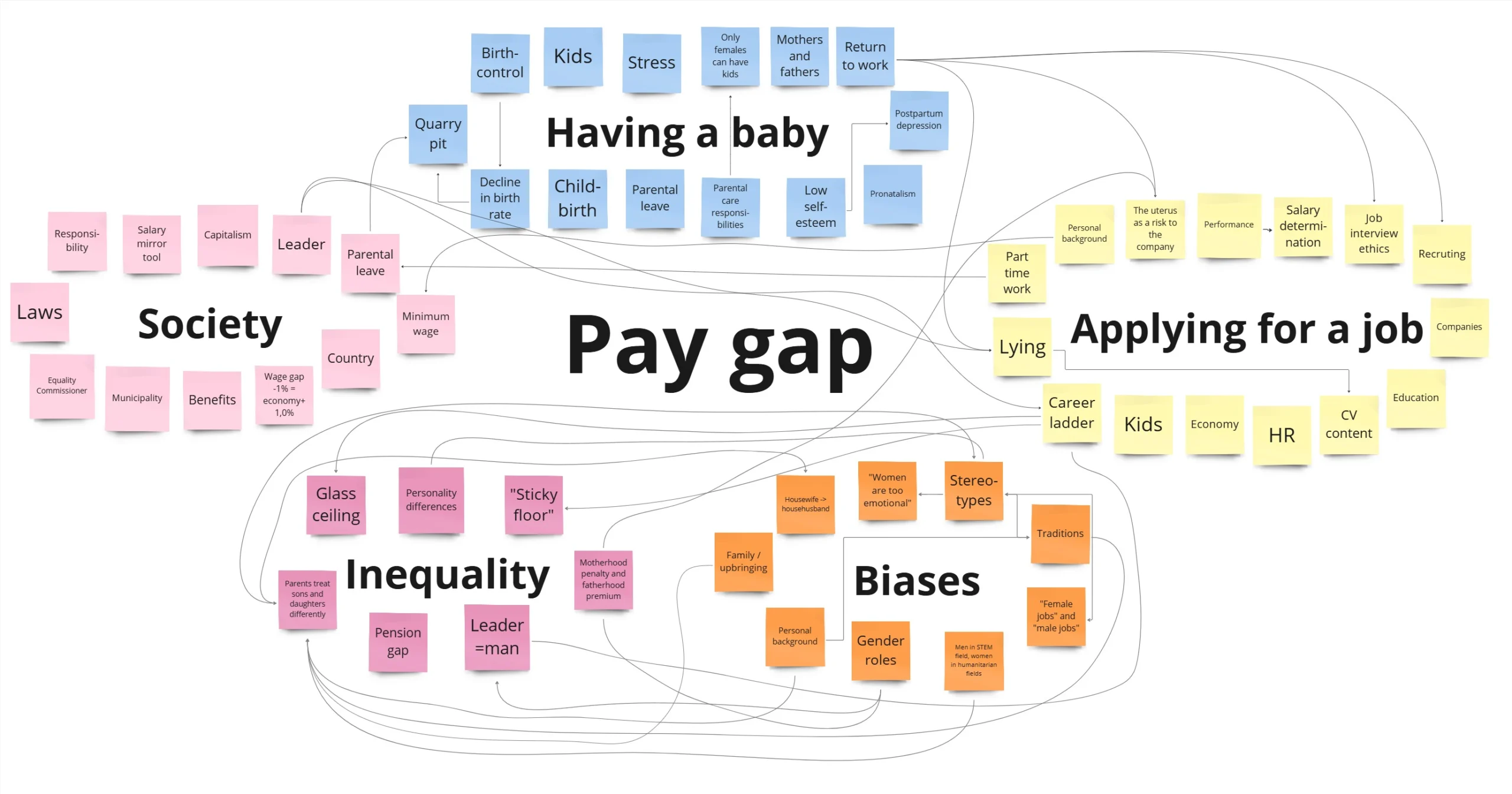

The challenge is to increase people's awareness of existing prejudices and biases in the local context. We decided to research the gender pay gap, and specifically how gender biases and unequal treatment based on gender can contribute to it.

Gender Pay Gap

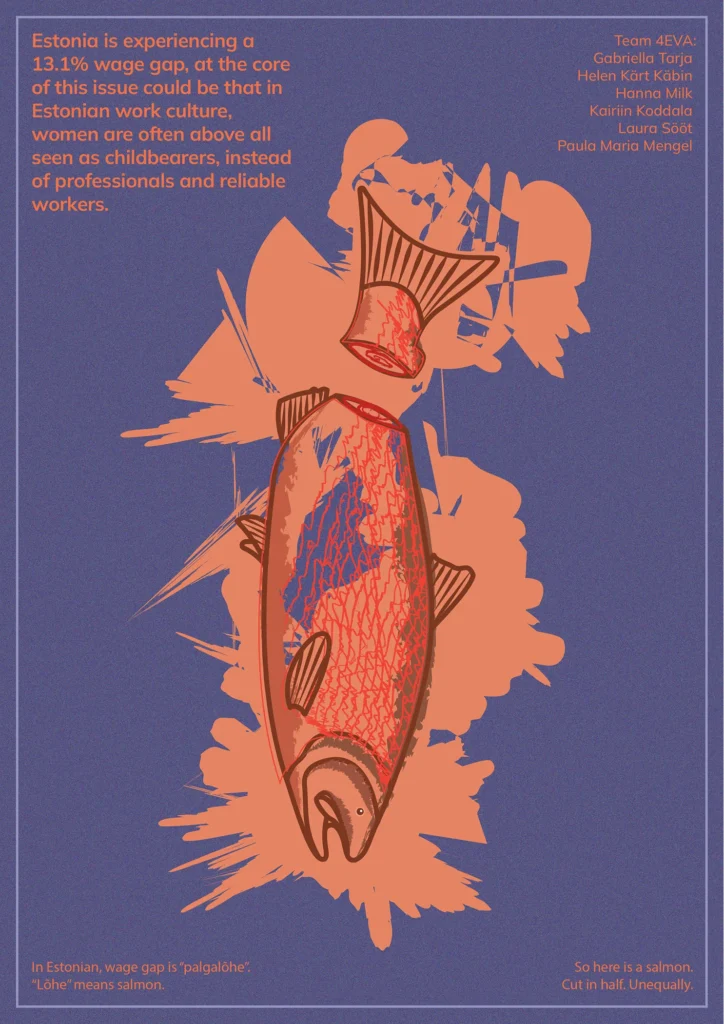

Estonia has had a remarkably high gender pay gap for decades. In the 1980s, it had the highest pay gap in the Soviet Union – 41%. In 2022, Estonia earned the same title within the European Union, with a gender pay gap of 21.3%.

Although it is now 13.1%, this is still significantly higher than in many other countries – and to the detriment of women.

Why is the Gender Pay Gap an Issue?

Gender-unequal income limits women's career prospects. As a result, many have to choose between family and career, which leads to greater dependence on partners and makes leaving abusive relationships more difficult.

When women earn less, the family's total income is also lower, and consequently, children's future opportunities are limited.

Reducing the gender pay gap improves employee productivity and overall well-being, which means they are less likely to leave their jobs. At a community level, lower wages for women lead to reduced tax revenue, increased public sector spending, and greater poverty among older women.

What Causes the Gender Pay Gap?

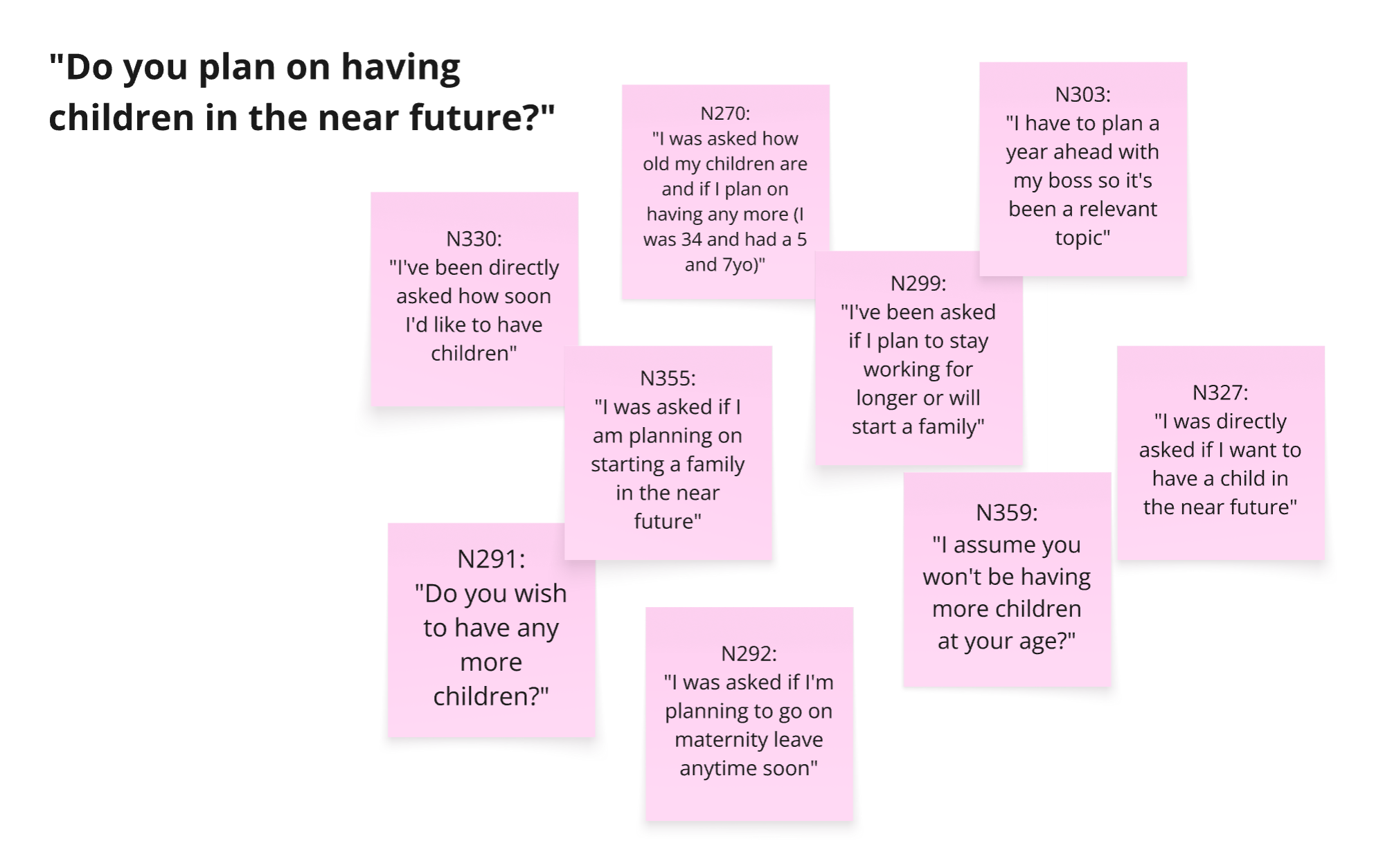

There are several reasons, but most of them boil down to prejudice and unequal treatment based on gender. Since 2004, Estonia has had a Gender Equality Act, which states the following: "An employer's actions shall also be considered discriminatory if, when making decisions listed in subsection 1 of this section, they disregard another person due to pregnancy, childbirth or any other circumstance related to their gender." Regardless, Estonian women are often asked about their personal relationships and family plans during job interviews, and there are times when this makes up the majority of the conversation.

It is also often noted that women are simply not as risk-averse as men and do not ask for salary increases or promotions as boldly. In this regard, it could be a vicious circle where women do not dare to ask for promotions because they know what is expected of them and anticipate that the answer may be different from what men receive, due to prejudice.

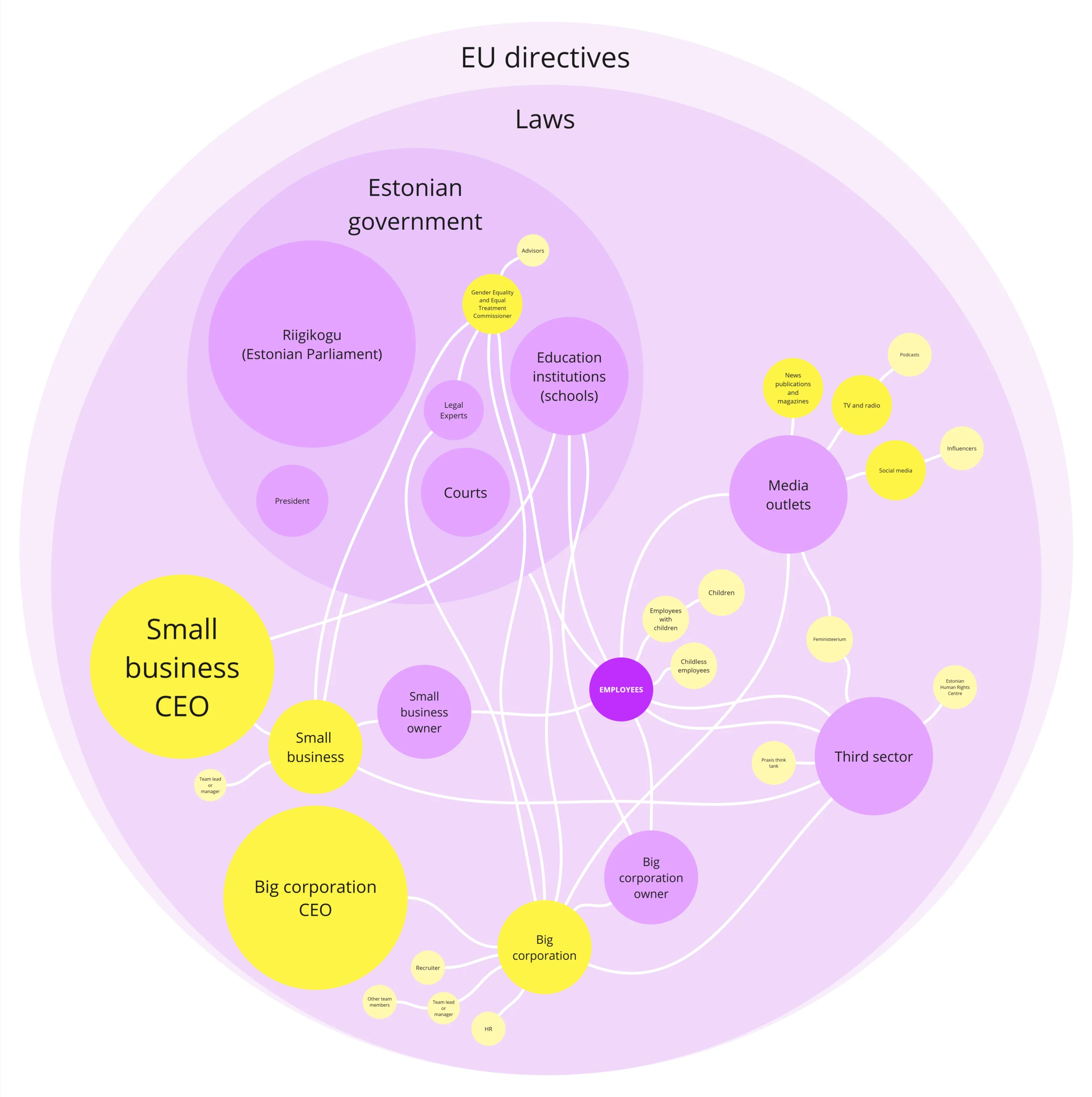

We created a system map illustrating the relationships between the key products, services, processes, and stakeholders surrounding the gender pay gap issue.

Women in Tech

We attended a Bolt Women in Tech lecture where Helen Biin, Civitta's gender equality and DEI expert, spoke on the topic: "Breaking Barriers, Building the Future: Women Shaping the Tech Industry."

We learned that gender-diverse companies:

- Are more profitable.

Companies with gender-diverse executive boards are 21% more likely to be profitable. Companies with gender-diverse teams are 39% more profitable. - Are 73% more likely to make good decisions.

Gender-diverse companies also have better risk management and make superior decisions because the more diverse the team members are, the longer it takes to reach a decision. As a result, everything is discussed more thoroughly. - Are more innovative and more responsive to market changes.

Care Responsibility

A report from the think tank Praxis, "What is the Cost of Unpaid Care Work?", reveals that women perform 70% more unpaid care work in society than men.

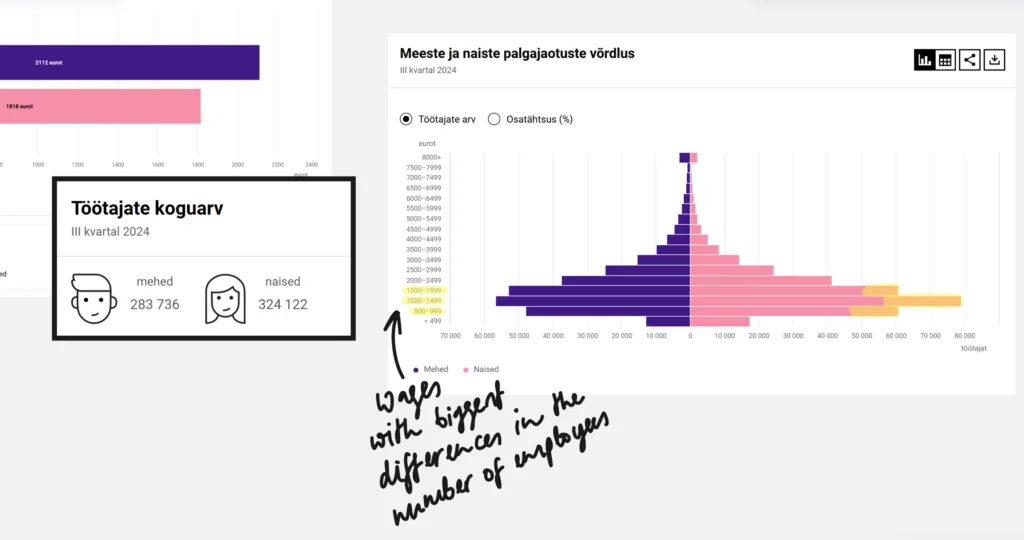

According to data from 2024, there are 40,386 more women working in Estonia than men, and the majority of those women are in lower salary brackets.

It's also mostly assumed that women will take parental leave – according to Statistics Estonia's 2021 data, 4.18% of men and 95.82% of women take parental leave. This creates a situation where, when a young woman applies for a job, it's taken into account that she might soon need to leave work for an extended period. If a company has to choose between a young woman and a man with equal experience in the field, it's a smaller risk for the company to hire the man, because the likelihood of the man going on parental leave is significantly lower. Women of childbearing age are therefore at a disadvantage when applying for jobs.

Secondly, women returning to the job market after parental leave have an unexplained gap in their CVs, which they are advised not to explain honestly. Mothers with young children are also not preferred, because children require a lot of attention and care and can often fall ill.

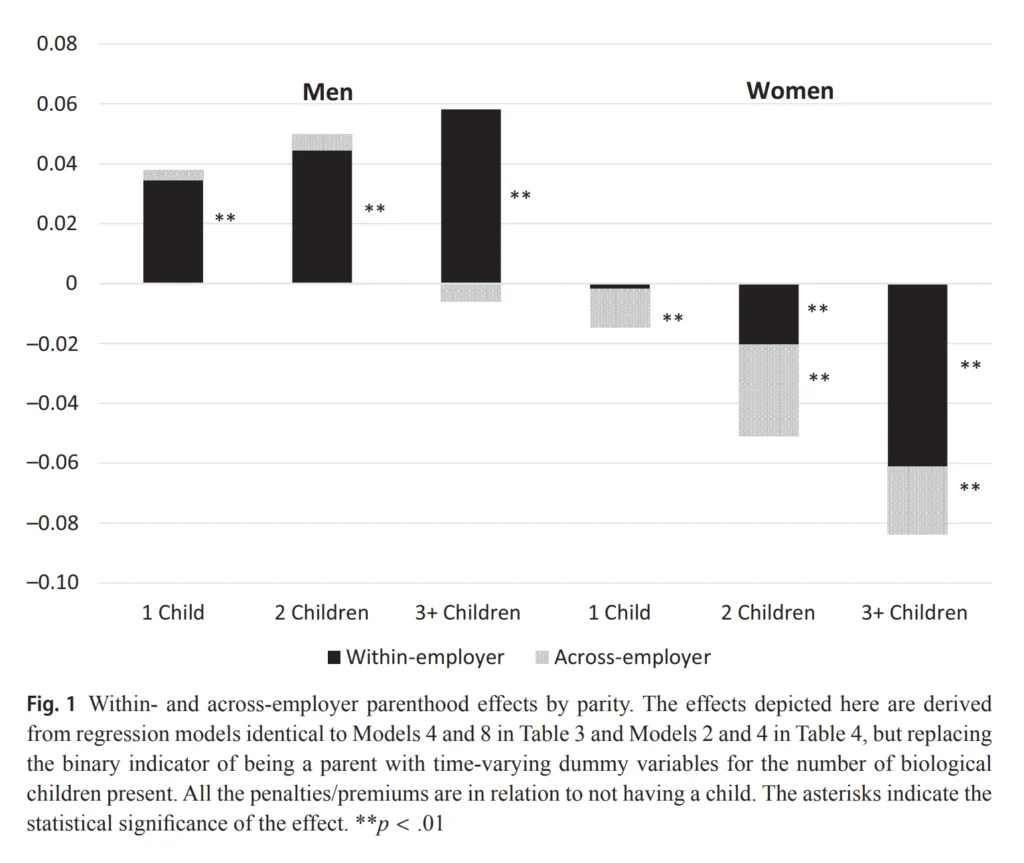

After parental leave, a woman returning to the same job faces an "motherhood penalty," meaning a change in her employment income compared to before becoming a parent. On average, mothers' employment income is a third lower seven years after childbirth than it was before the child's birth.

It has also been found that for men, this is replaced by a "paternity premium," the reason for which is simple: since the woman is expected to handle the care, it is believed that the man is now more motivated to work diligently due to the child, to provide for the growing family.

Wei-hsin Yu, Yuko Hara (2021)

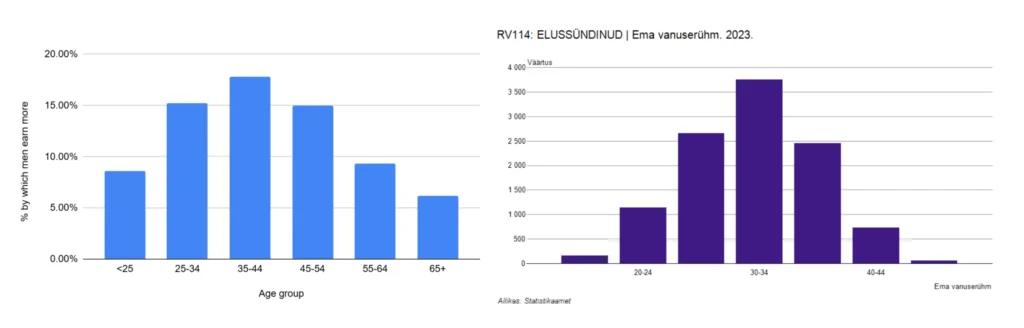

Using data from Statistics Estonia, I compared the income gap between Estonian men and women in different age groups. I noticed a sharp increase between the ">25" and "25-34" age groups.

I was interested to see if the difference in salaries might grow significantly at this age, as this is often when people first have their children.

Ethnographic Research

To test the hypotheses formed regarding the connection between the gender pay gap and biases, we began investigating gender biases in Estonian recruitment processes. We established the following research questions:

- What are the current perspectives on the differences between men's and women's work cultures?

- How does the recruitment process differ between genders?

- What impact does having children have on the recruitment process?

- How does having children affect the salaries of men and women?

Survey

We put together a survey in which we focused on three key areas:

- Whether personal relationships and children were asked about during job interviews;

- Whether family plans were asked about during job interviews.

- Whether and how having children has affected applying for jobs.

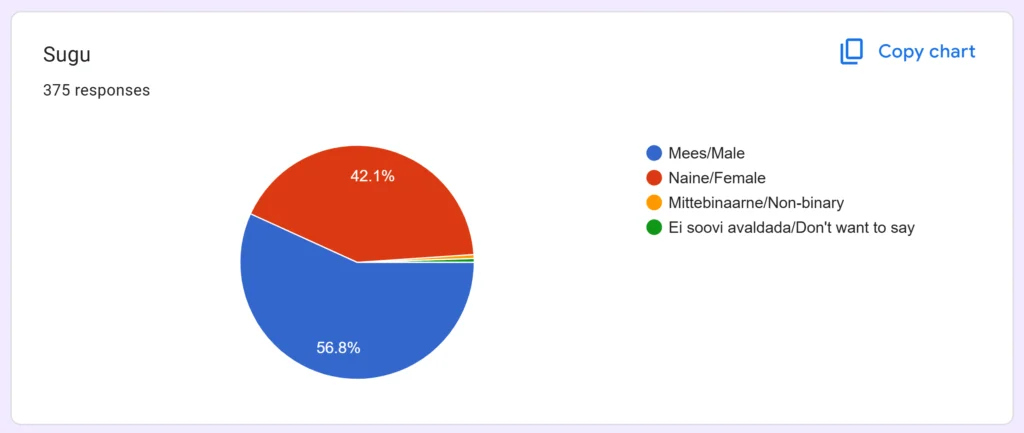

Initially, around 90% of respondents were women. To reduce the resulting bias in the research findings, we shared the survey directly with men and in a large Facebook group for fathers. Ultimately, we collected 375 responses, with men accounting for 56.8% of them.

The results showed that questions about relationships, children, and family plans are asked of both men and women more or less equally. The difference emerged in the way questions about family plans were posed: for women, the focus was specifically on pregnancy, while men were asked about general plans.

When we asked if children had impacted their work life, both women and men again answered that they had. Both wrote about the need for greater flexibility regarding working hours and location. However, the positive impact of children on work life only emerged from men's responses, where they wrote that having many children led to being considered a success and that the presence of children allowed them to negotiate a more flexible work-life balance and higher salaries.

We received longer responses from several mothers who wrote about their negative experiences of applying for jobs as mothers. Based on this, we also shifted our research focus more towards motherhood topics to investigate how maternal status affects career opportunities.

Interviews with Experts

We consucted 5 hour-long interviews with the following experts:

- Liisa Oviir, Advisor to the Gender Equality Commissioner;

- Two private sector recruiters;

- A public sector recruiter;

- Investor Kristi Saare.

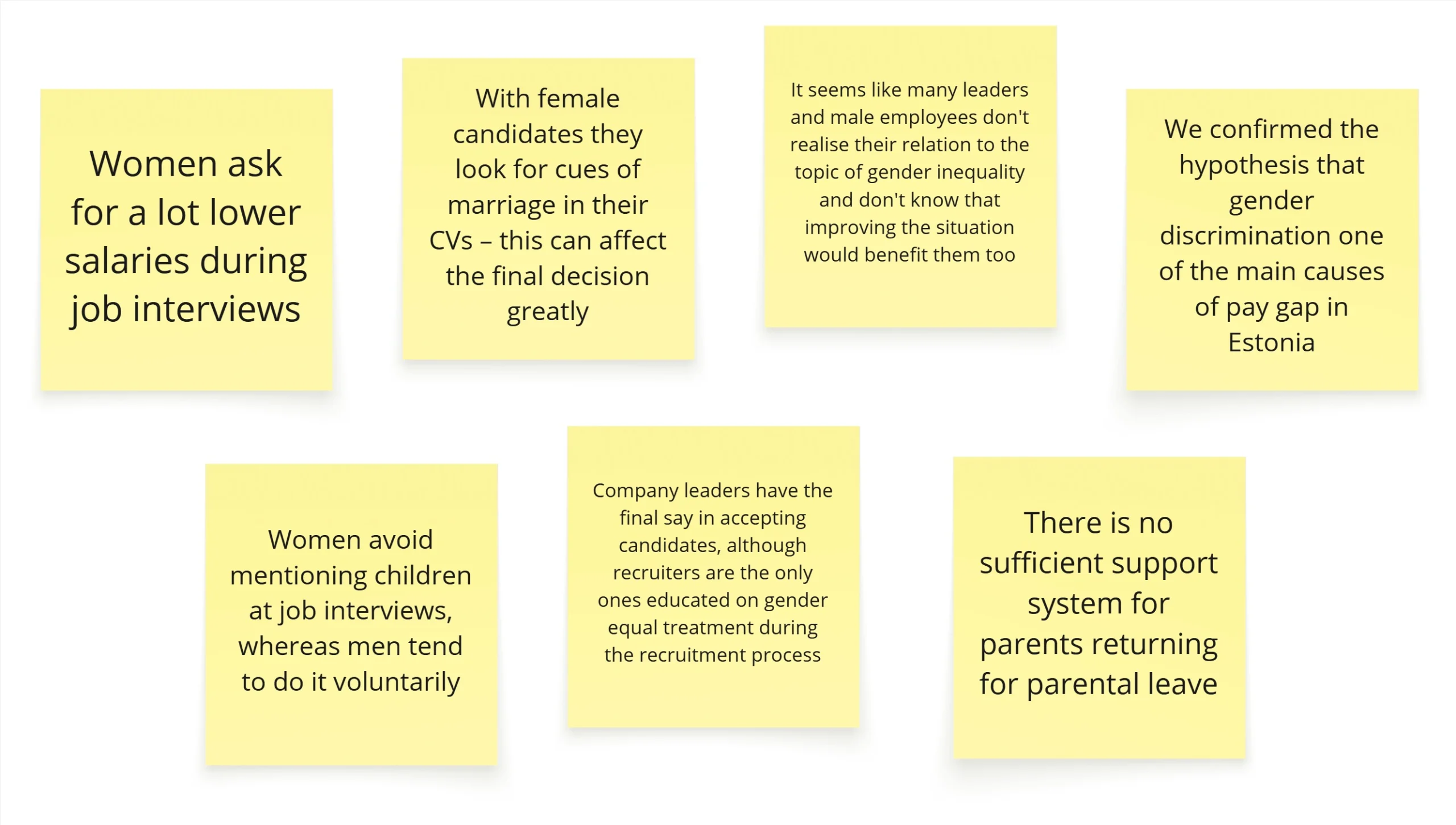

Key Insights from Interviews:

Stakeholder Map

This illustrates the interconnectedness of stakeholders influencing gender inequality within workplace culture. Stakeholders with a greater scope of influence are represented by larger circles.

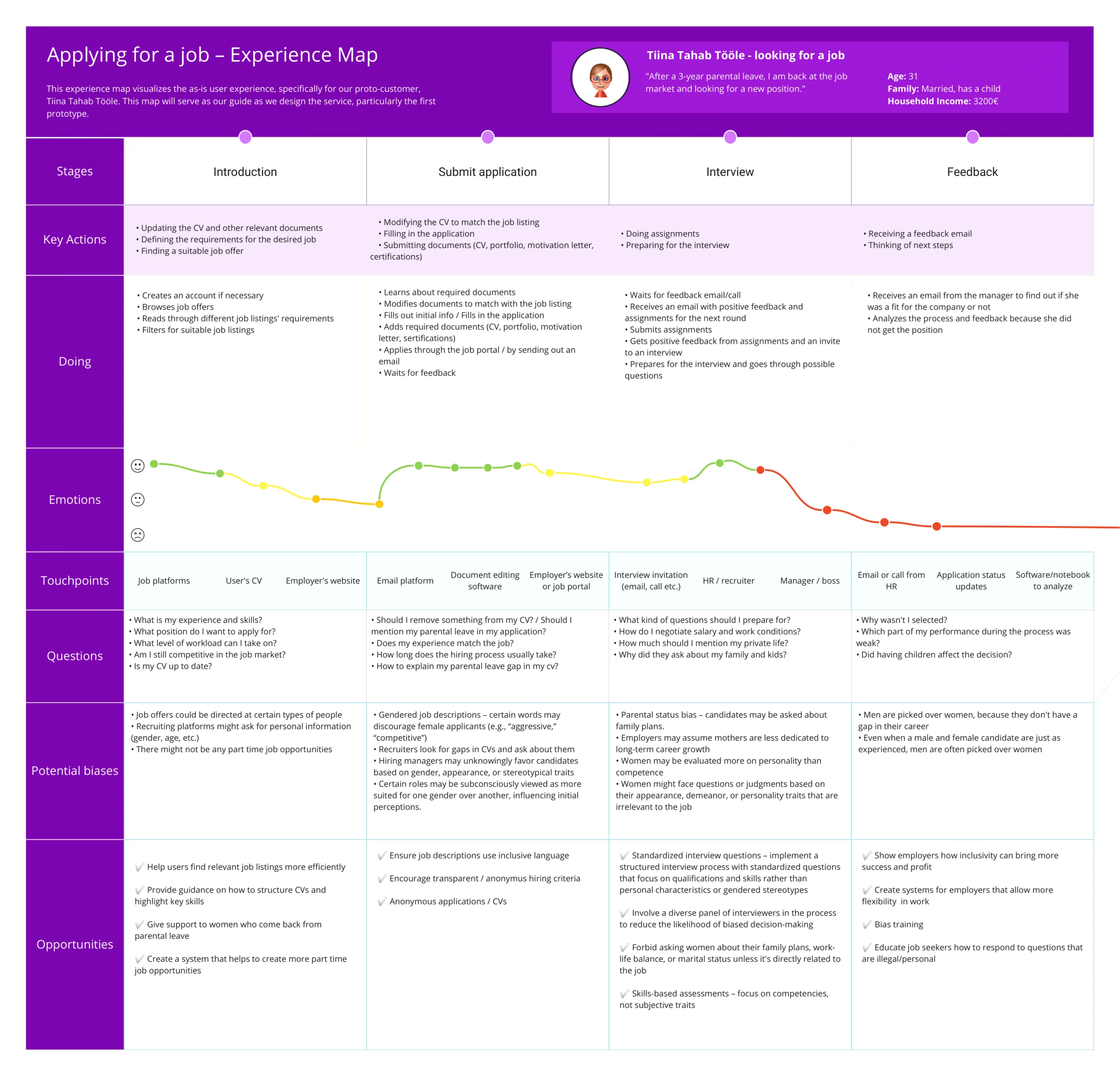

Experience Map

The experience map illustrates the job application process from the perspective of a mother of a young child returning to the job market after parental leave.

What's next?

As the next step, we'll conduct a co-creation workshop with various stakeholders to jointly seek a solution to the problem. As part of the project, we'll design a service design solution.